1- PRESENTATION

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

TRANSCRIPTION:

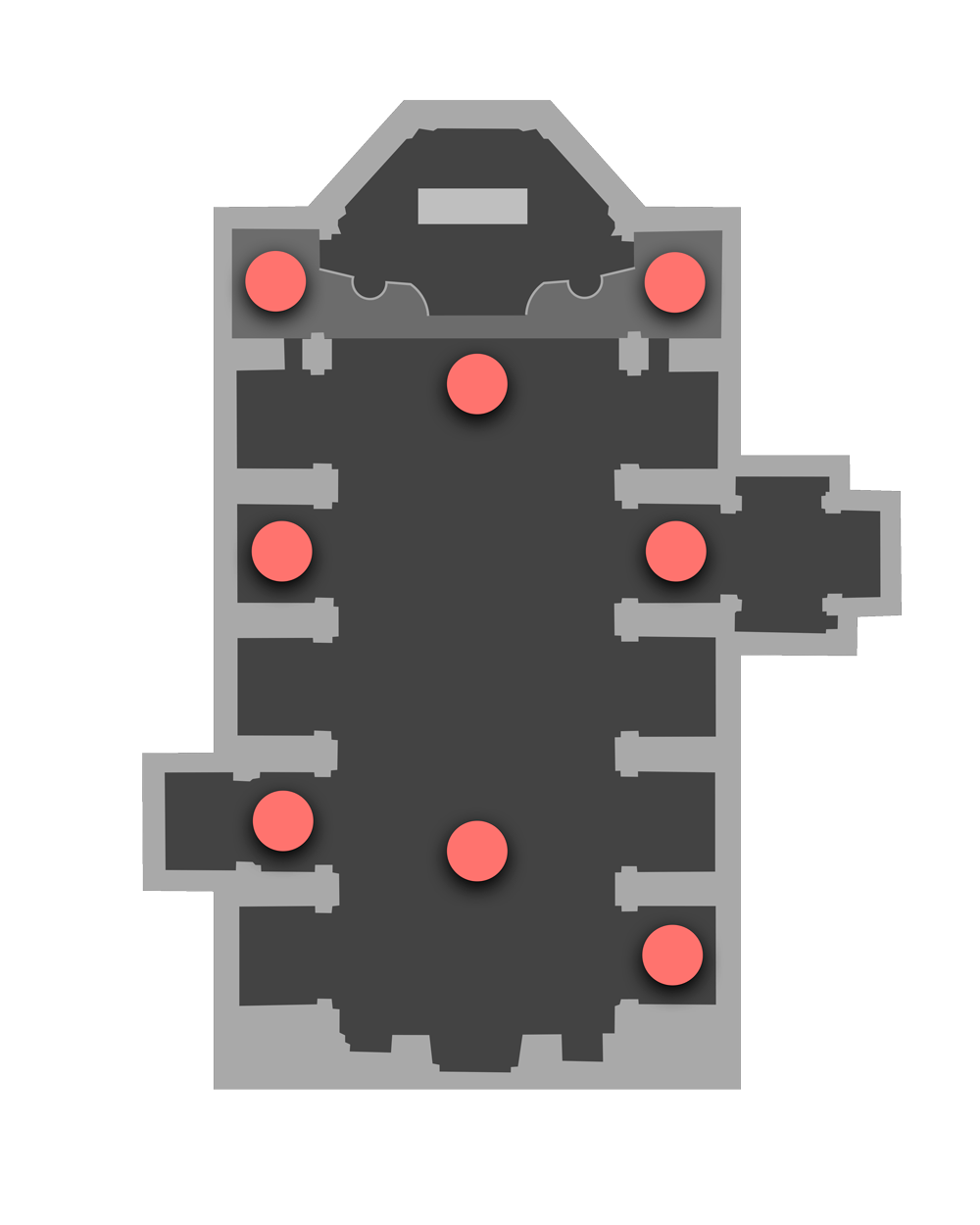

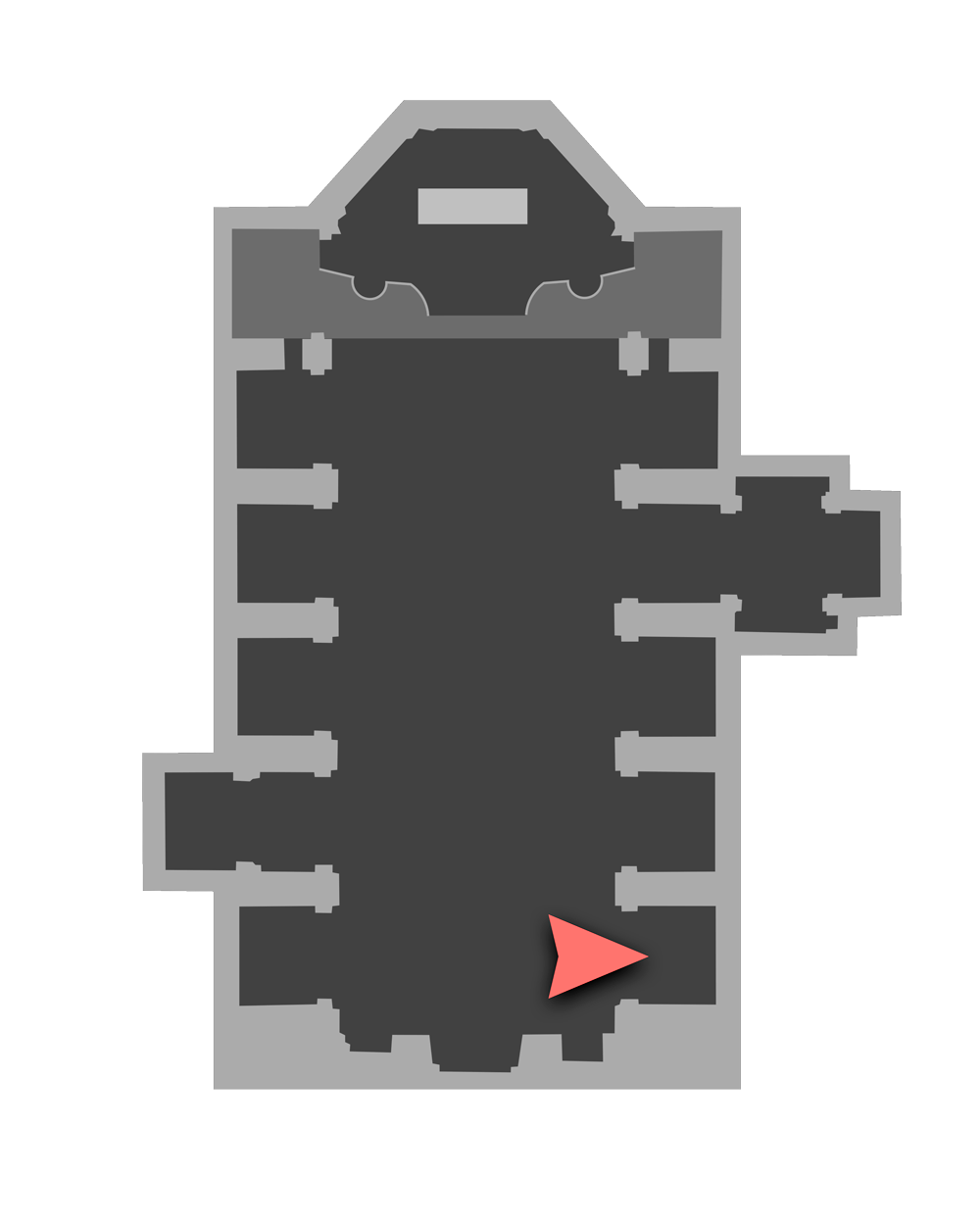

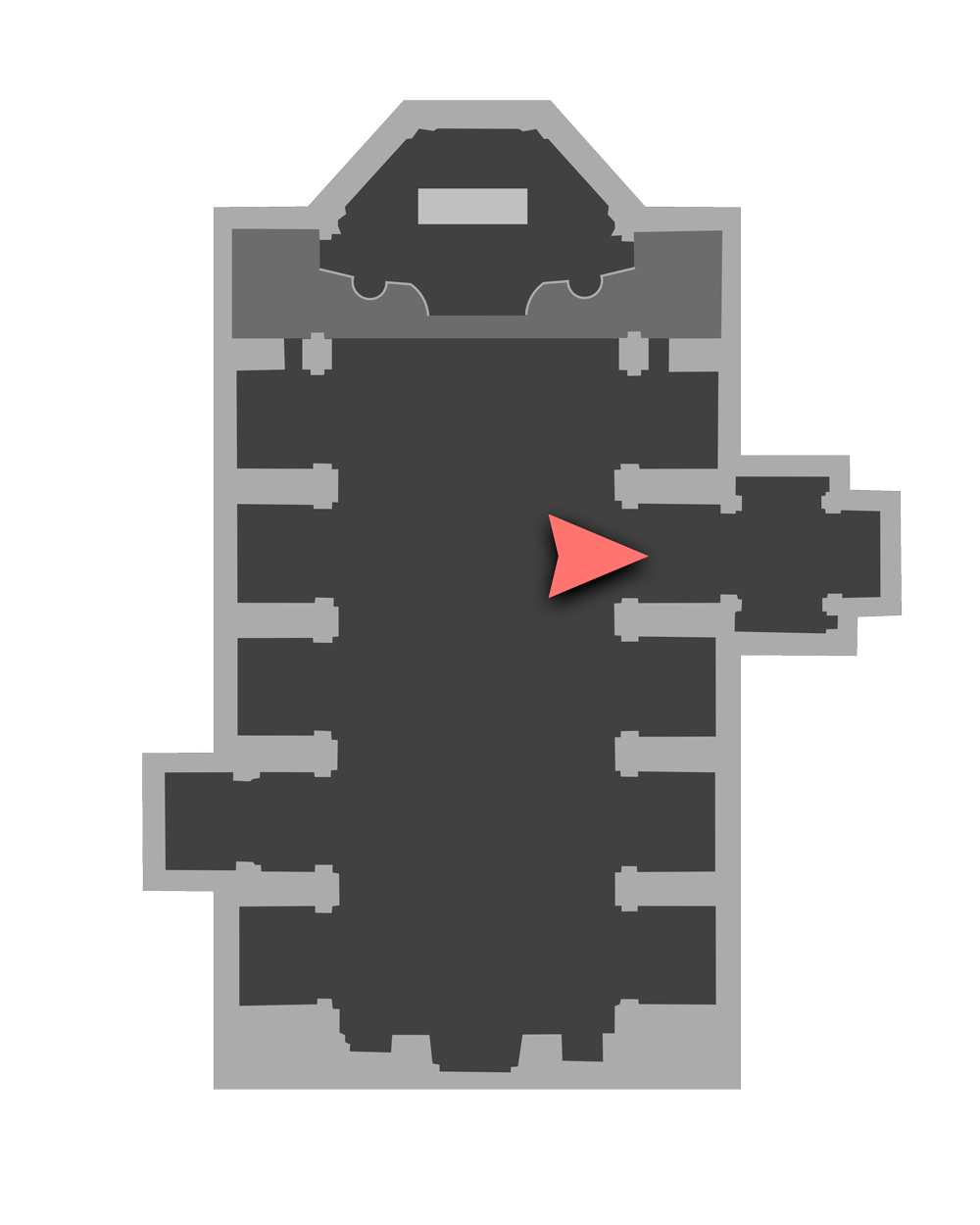

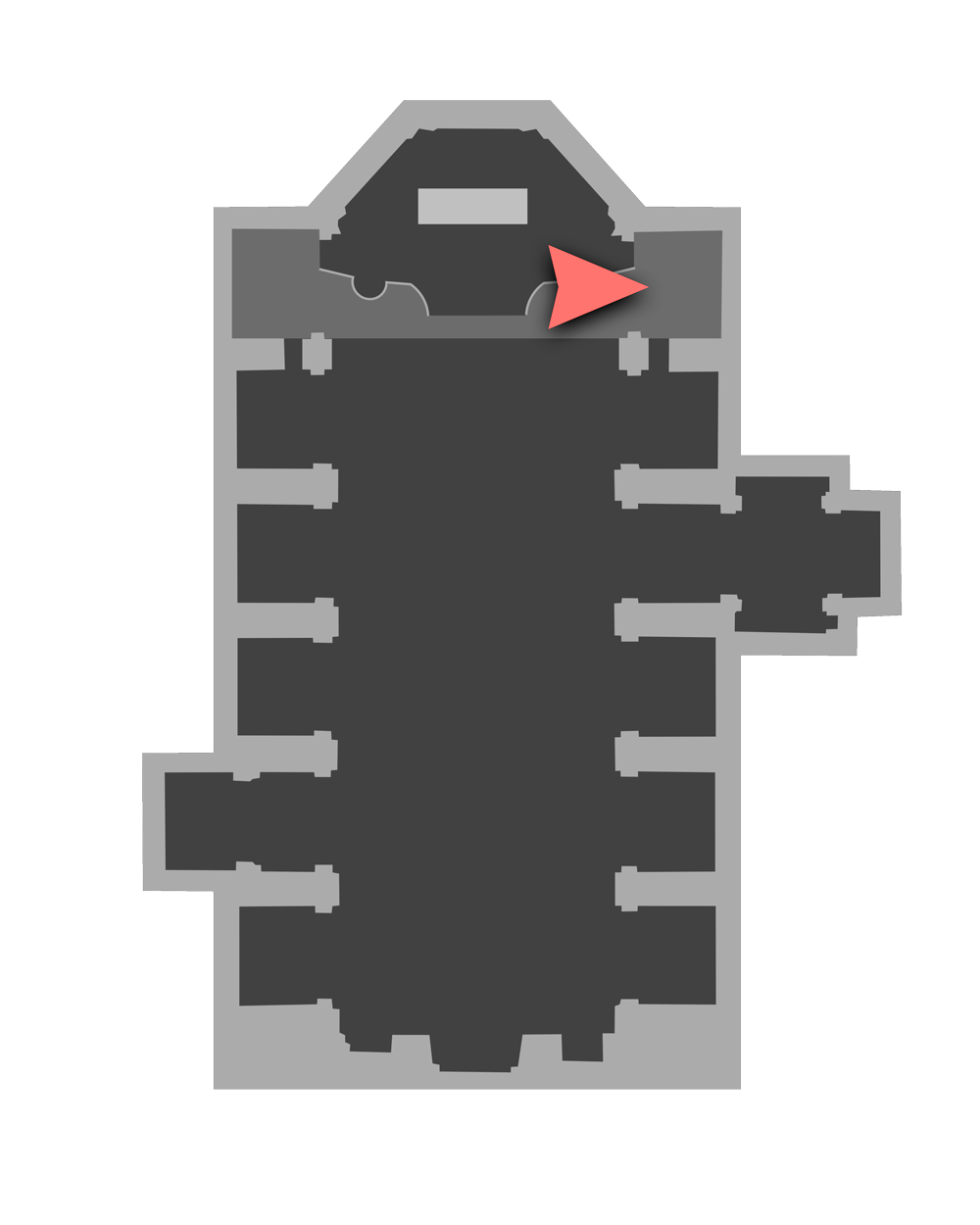

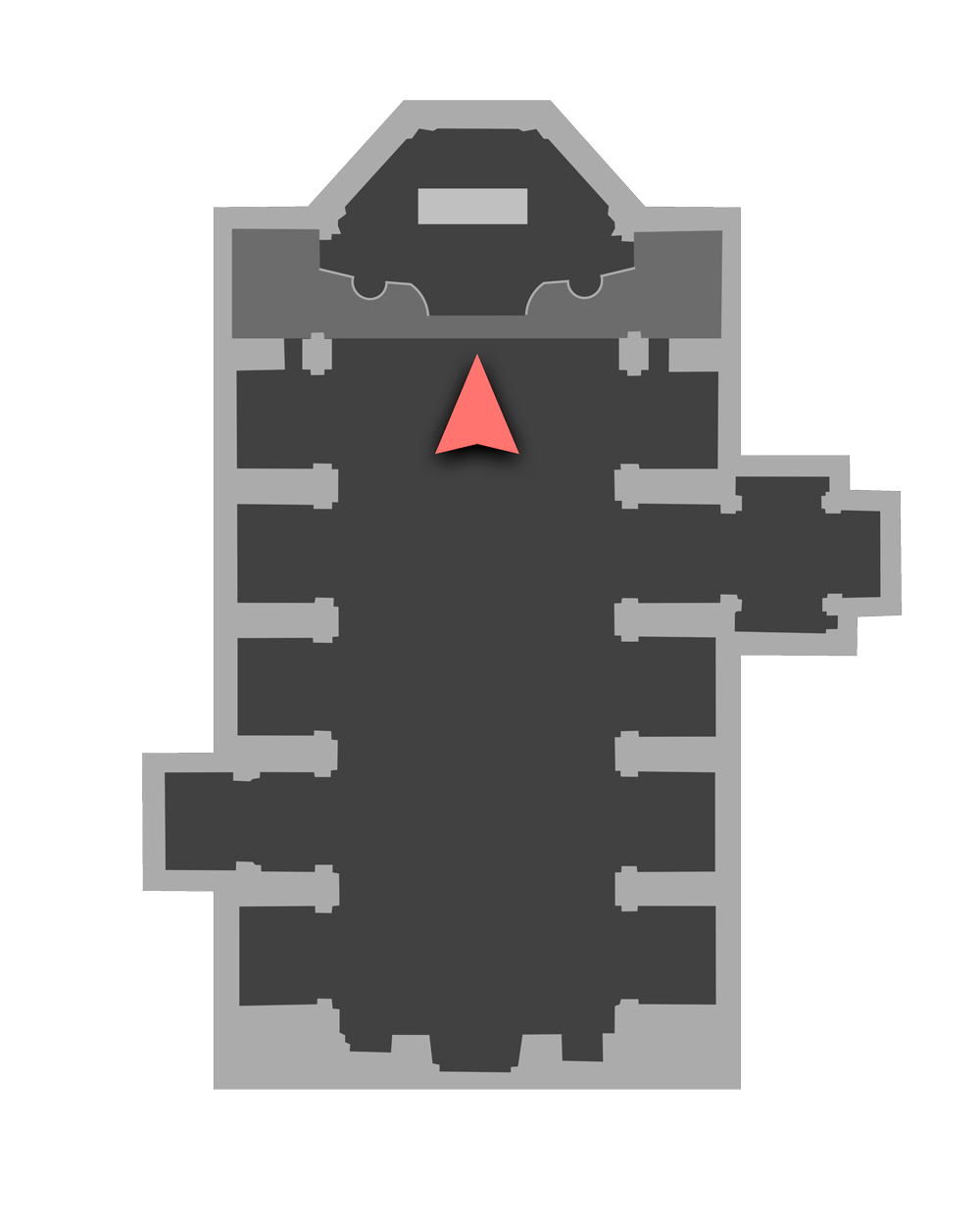

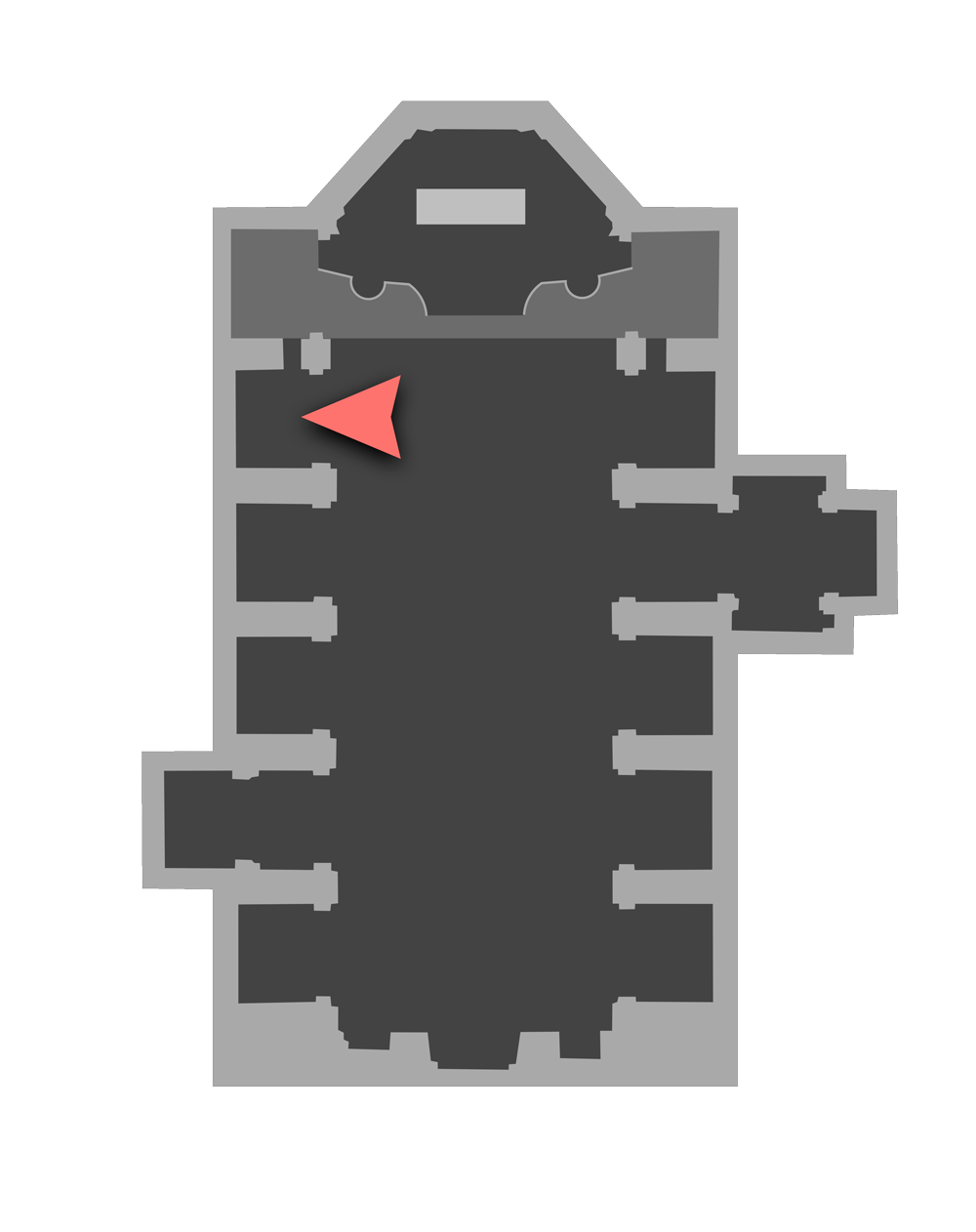

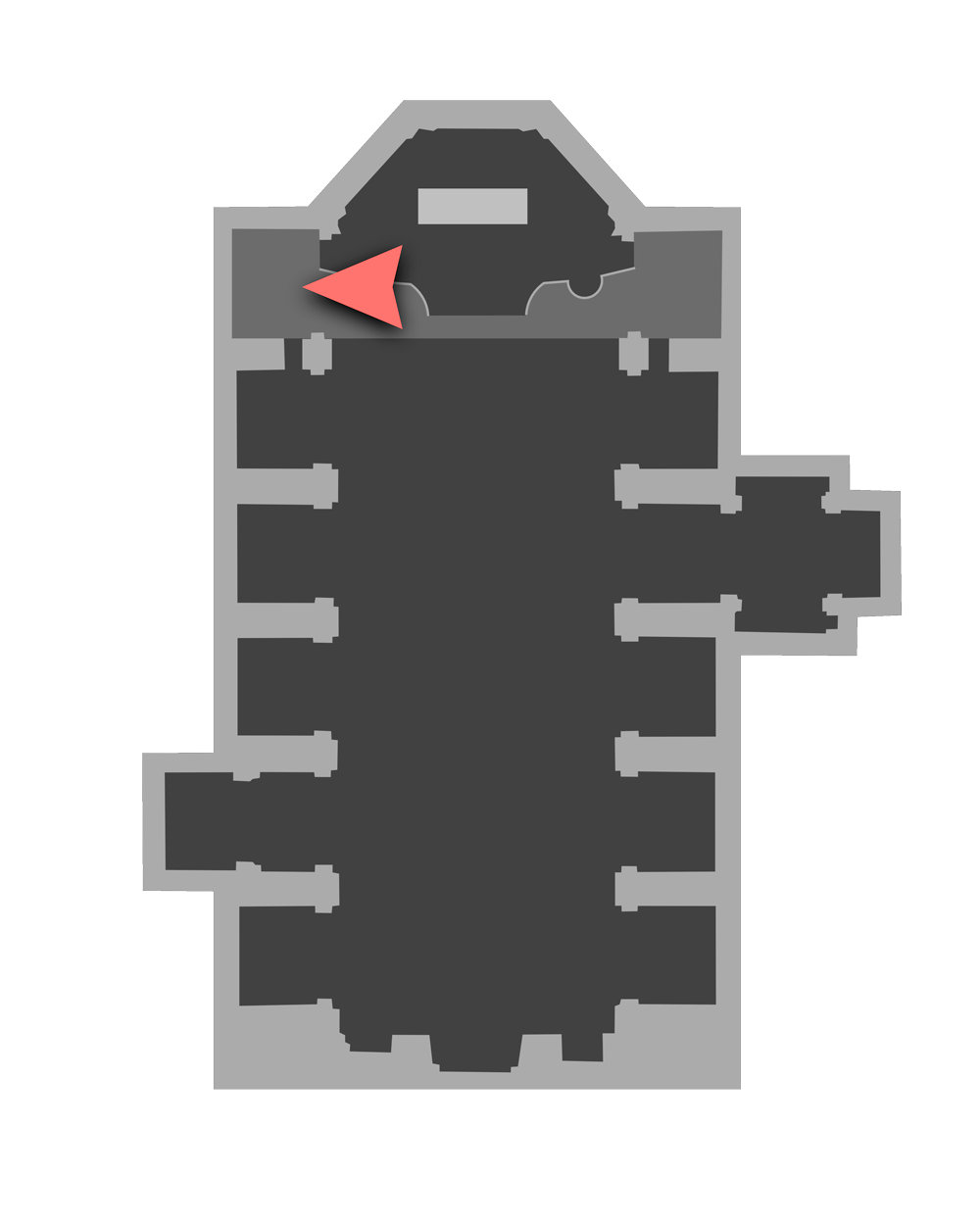

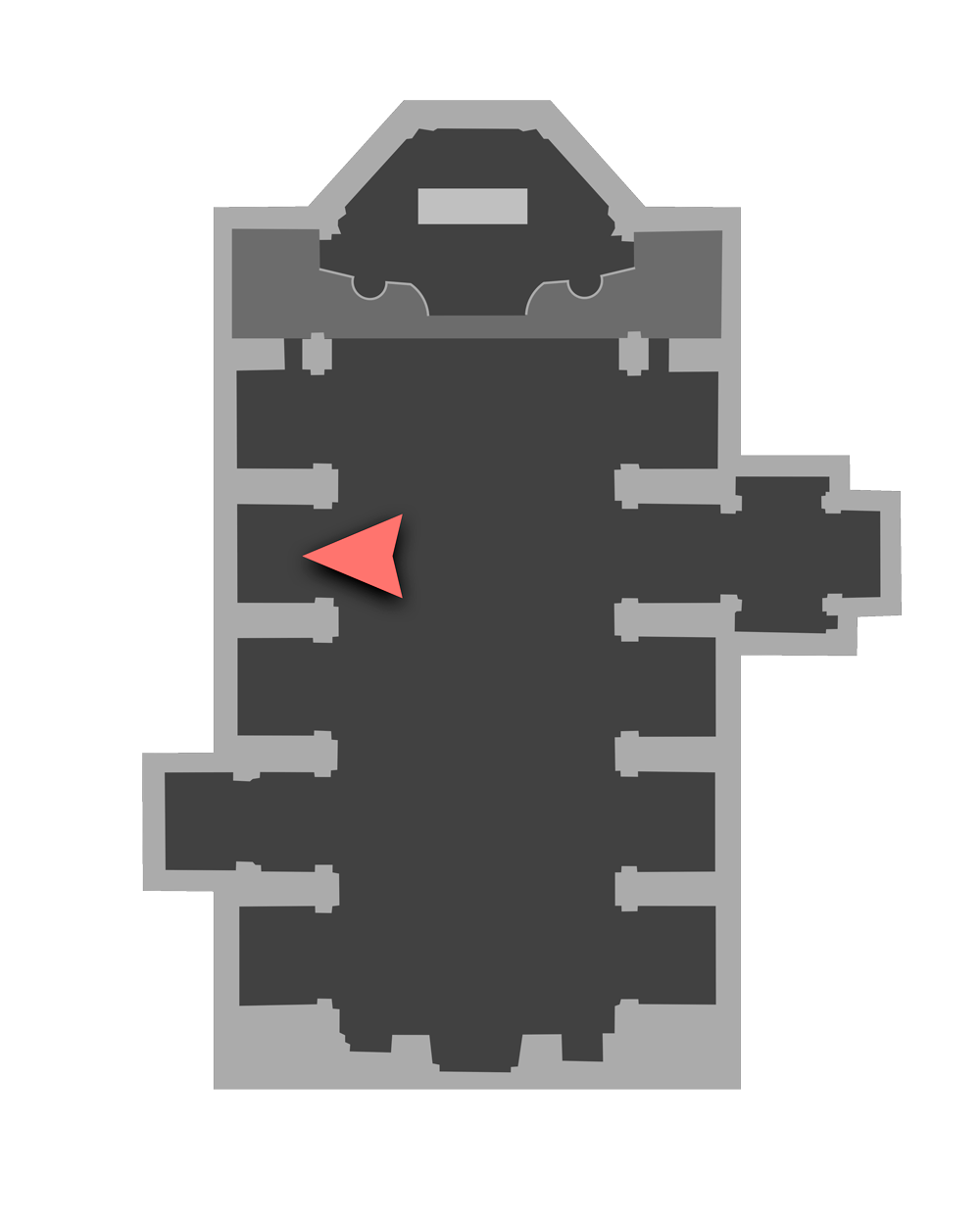

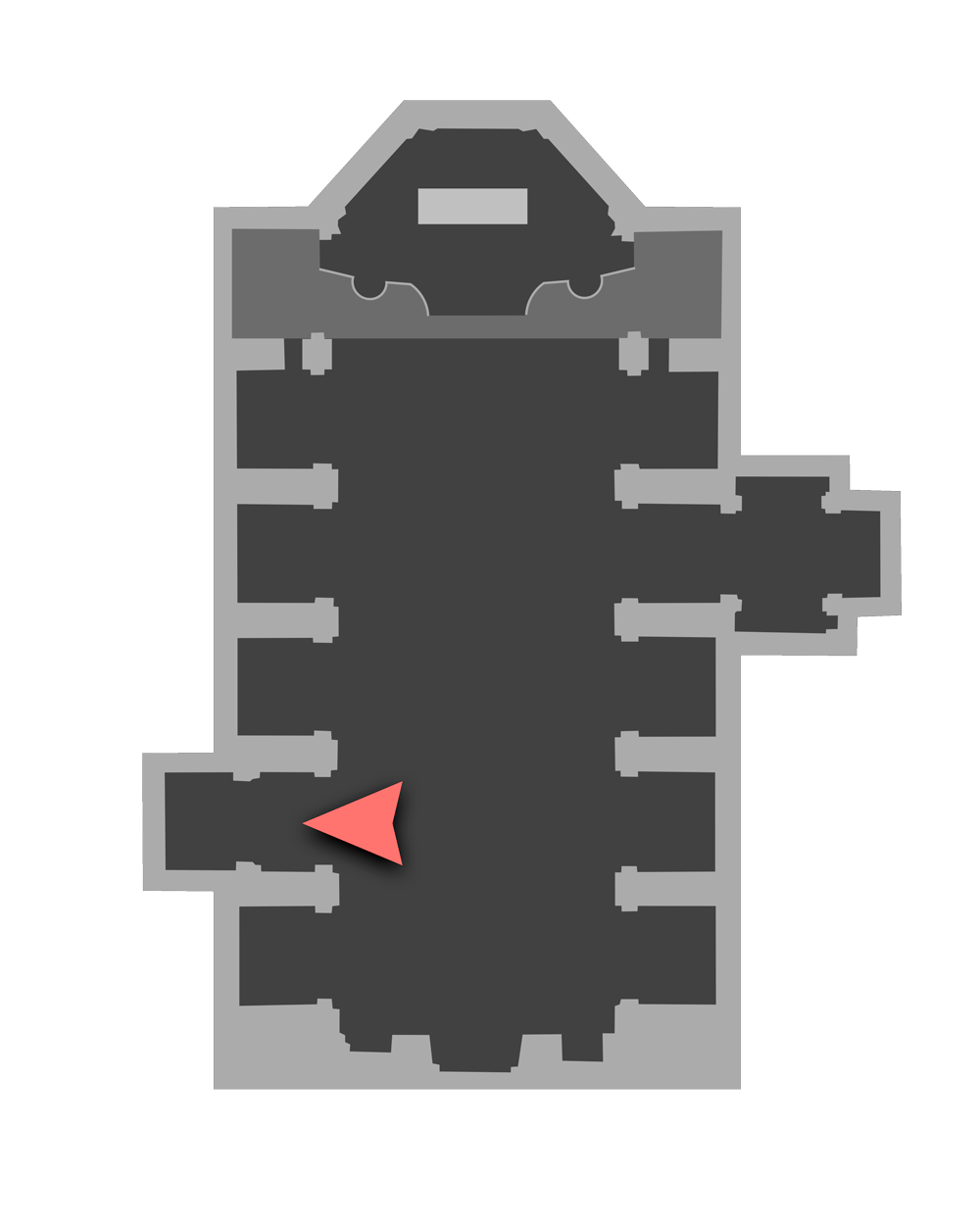

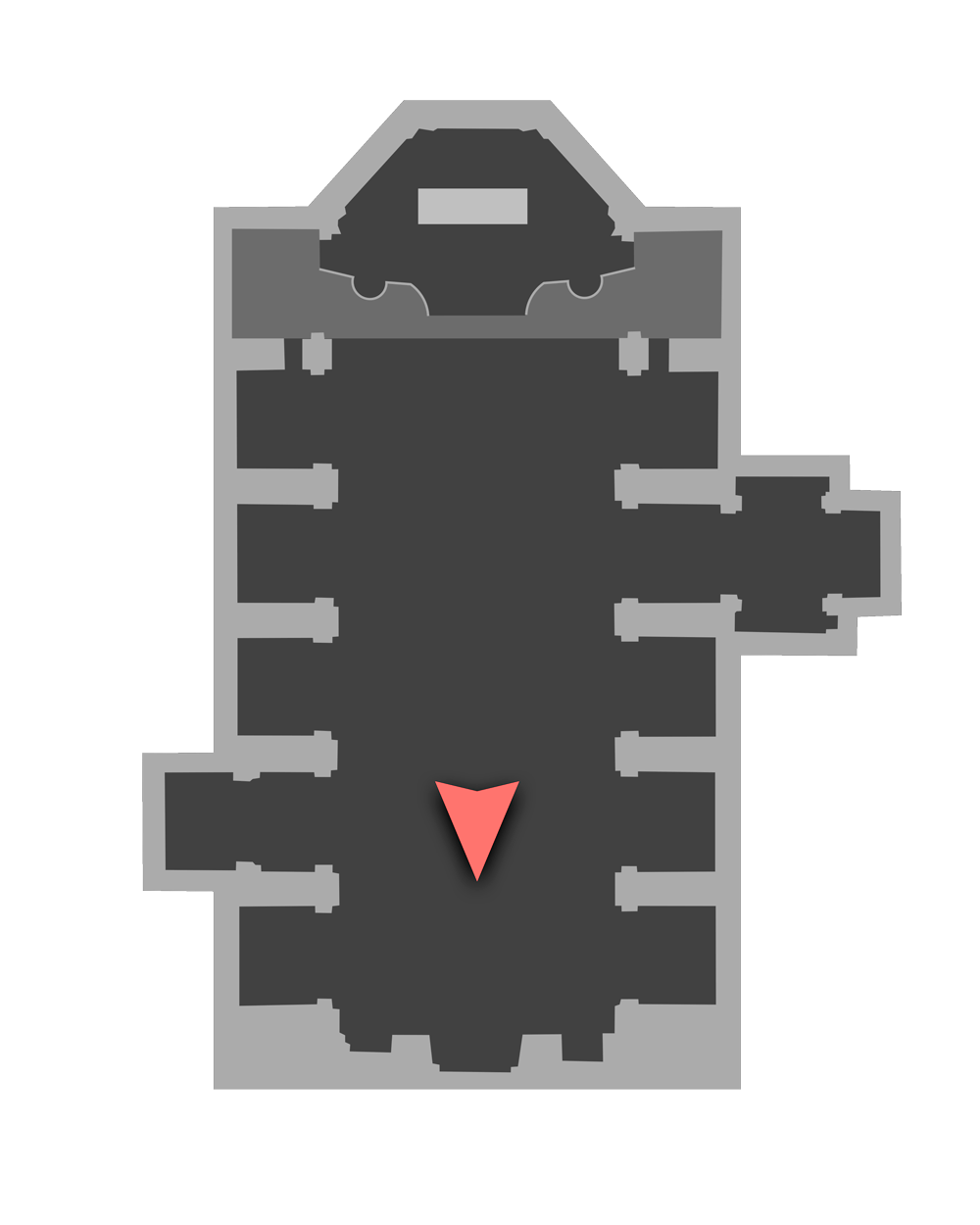

CHURCH FLOOR PLAN AND DOORWAY

Welcome to the former parish church of San Andrés, now known as San Juan de la Cruz.

Built on the foundations of an old Arab mosque, its construction dates back to the 13th century, a period of expansion of the Crown of Aragon under King James I. It took the name of San Andrés in honor of Andrew, King of Hungary and father of Queen Violante, his wife.

However, almost nothing remains of that Gothic construction. Its layout was transversal to the current axis of the church. The main doorway opened next to the bell tower, which is the only preserved vestige of the original church. Its current appearance is the result of subsequent renovations carried out between the 17th and 18th centuries.

Main entrance of the church

The current main entrance is located at number 6 Poeta Querol Street and was built between 1684 and 1686. It is attributed to Juan Bautista Pérez Castiel, an exceptional architect. At the top of the lintel is a cartouche with an inscription alluding to the ownership of the church and the date of its construction. The Solomonic columns flanking the entrance, richly adorned with laurel, are noteworthy. Until 1936, a sculpture representing Saint Andrew stood at the top of the entrance, but today only the crosses, a symbol of his martyrdom, remain.

Image of the entrance to the chapel of Father Simó

Looking straight ahead and to the left of the main entrance, we see a bricked-up door. This was the entrance to the chapel dedicated to Father Simó. This is a much simpler entrance, as it dates from the first renovation of the church in the first half of the 17th century. The Eucharistic emblem is found at the top.

Francisco Jerónimo Simó was born in Valencia, the son of a French carpenter and a servant. After being orphaned at a very young age, he had to work in many houses to survive. His life changed when he entered the household of the theologian Juan Pérez. In addition to showing signs of a religious vocation, he came into contact with a large number of figures from the Valencian spiritual world. Finally, in 1603, thanks to the patronage of Don Jerónimo Núñez, lord of Cella and Samper, Francisco Jerónimo obtained an ecclesiastical benefice in this former parish of San Andrés. He soon became popularly known as Father Simó, enjoying a certain reputation as a saint during his lifetime. After his death in 1612, he was buried in this parish. The attempt to beatify Francisco Jerónimo Simó after his death unleashed one of the most significant phenomena of religious and social upheaval, not only in Valencia but also at court and in the Holy See. Although the beatification ultimately failed, Father Simó continued to be venerated long afterward. Once his worship was banned, this chapel changed its use and became the original communion chapel.

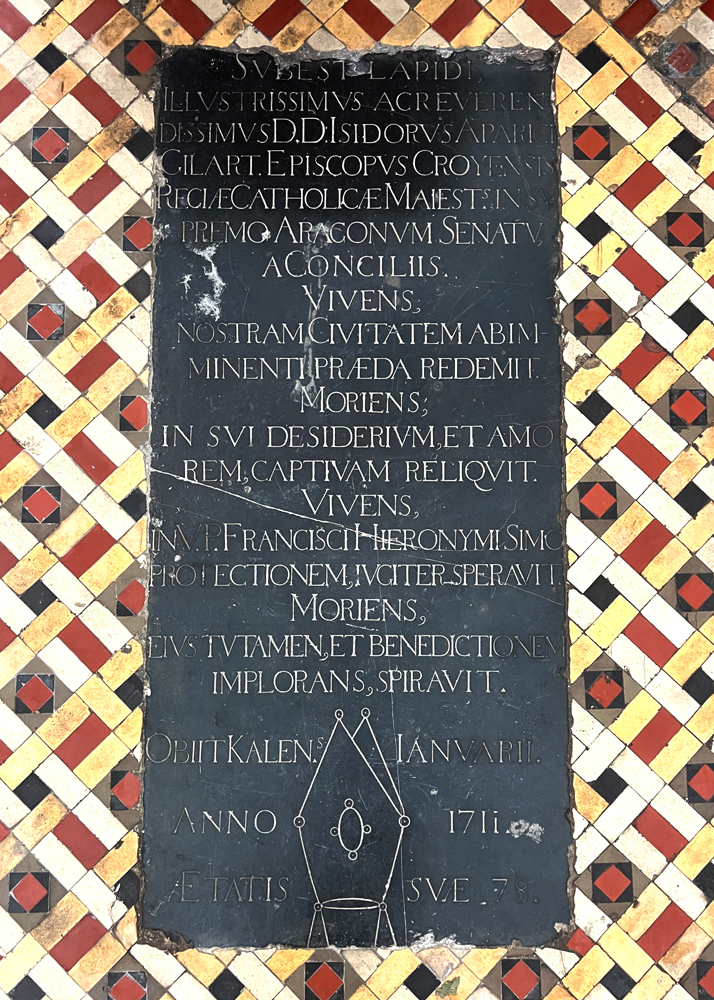

Tombstone of Father Simó, located in the Sacristy

There is also a third entrance from this same street, located to the right of the main entrance if you look straight ahead. This is the entrance to the current Communion Chapel. The construction of this chapel was completed in 1741 and was originally dedicated to Saint Peter, patron saint of fishermen. In fact, much of this work was funded by this brotherhood. This is no coincidence, as this parish belongs to the old fishing district of Valencia.

Image of the Communion Chapel cover

Parish of Saint Andrew or Parish of Saint John of the Cross? It’s a fairly common question among Valencians.

In 1902, the parish of Saint Andrew moved to Colón Street. Furthermore, after the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), the church had been completely abandoned and was on the verge of demolition. Just as Manuel González Martí (Valencia, 1877-1972) saved the neighboring palace of the Marquis of Dos Aguas from demolition, the initiative of art historian Elías Tormo (Albaida, Valencia, 1869 – Madrid, 1957) resulted in the former parish of San Andrés being declared a National Monument on April 10, 1942, thus saving it from destruction.

The ownership of San Andrés, as mentioned above, was granted by King James I from its founding until 1952, when the church became part of the Carmelite convent of San Juan de la Cruz, thus permanently changing its ownership.

HISTORICAL CONTEXTThe current church was the initiative of Archbishop Juan de Ribera, who ordered its construction from scratch between 1601 and 1615. At that time, it was decided to change its orientation to make it larger. As we can see in the plan, the church now has a single nave, divided into five bays with side chapels between buttresses. The apse is polygonal. It was decorated with classicist style. However, nothing of that original decoration remains. Furthermore, some renovations have been carried out since then.

However, the most significant renovation took place between 1750 and 1765. A new Rococo decoration was introduced, unparalleled in Valencian lands, based on a profusion of stucco, gilding, and rocailles. Visiting «El Oro de San Juan,» with its countless hieroglyphic stucco elements, its gilding, and its paintings and ceramics, one experiences the emotions of Rococo art adapted to the 21st century.

The Rococo style is a decorative movement that developed in Paris in the early 18th century in the palaces and residences of the nobility. This style finds its origins in the decoration of the Palace of Versailles, where the superposition of moldings, rocaille, the use of pendentives, and arabesque sets of curved volutes in the shape of an «S» or a «C» are the dominant trend.

In the rest of Europe, it is worth noting that it was a style widely used in southern Germany, where it became the preferred architecture of the court. In Spain, Rococo art did not have much impact due to the preference for the Churrigueresque style. In Valencia, Rococo was also not very successful, as the taste for Baroque prevailed, especially in religious architecture.

In civil architecture, the French Enlightenment influence took hold among European kings and nobles, who wanted to found new academies of learning and renovate their palaces in the style of their neighboring country. The homes of the nobility were conceived as pleasant places to live, and only the elite who frequented palace celebrations experienced the ornate richness and joyful beauty of their halls. The proliferation of decorative elements was oriented toward the new sensibility, aiming to create a pleasant atmosphere that also reflected the wealth of its owner.

An example of this trend among the nobility of the period is Giner Rabassa de Perellós y Lanuza (Valencia, 1735-1765), the third Marquis of Dos Aguas.

In 1753, he founded the Royal Academy of Santa Bárbara in Valencia.

He was a benefactor of the temple’s renovation process, which fully embraced the new Rococo aesthetic principles of the period. Although there is no documentation to support this, numerous studies claim that the layout and design of the interior decoration were conceived by the brilliant engraver and painter Hipólito Rovira (Valencia, 1693-1765) and executed by his disciple, the sculptor and carver Luis Domingo (Orellana, Valencia, 1718-1767). The two had previously worked together on the renovation of the neighboring palace of the Marquises, with Rovira designing the façade, which was executed this time by Ignacio Vergara (Valencia, 1715-1776).

Luis Domingo not only worked on the palace of the Marquises of Dos Aguas, but also on the Basilica of the Virgin of the Forsaken and other Valencian parishes. He was director of the sculpture section of the Academy of Santa Bárbara in Valencia and, in 1762, was named a distinguished academician in sculpture by the Academy of San Fernando in Madrid.

We can conclude by saying that the church of San Juan de la Cruz is an aesthetic and formal continuation of the palace of the Marquis of Dos Aguas.

2- VERGARA CANVAS

TRANSCRIPTION:

We are at the entrance to the current Communion Chapel. The canvases located on the upper part of its side walls were painted by the painter José Vergara (Valencia, 1726–1799). The themes are related to the Eucharist.

The canvas on the left is titled The Triumph of Faith over Heresy, Envy, and Discord. In the center, dressed in pontifical vestments and accompanied by an angel bearing the silver and gold keys of the Primacy of Peter, an allegory of the Catholic Church is depicted, showing the people the faith. Blindfolded, she holds the cross and chalice, symbols of the main beliefs of the Catholic faith. Also visible is the allegory of Truth, a woman holding the radiant sun in her hands. At the foot of the allegory of the Church, the allegories of Heresy, Envy, and Discord shiver.

The canvas on the right represents a legend. The work is titled Rodolf of Habsburg Gives His Horse to a Priest to Carry Viaticum. In the Catholic religion, viaticum is the sacrament of the Eucharist administered to a sick person in danger of death. This legend tells of how Count Rudolf, while hunting, came across a priest trying to cross a river carrying viaticum. Without hesitation, Rudolf of Habsburg gave his horse to the priest and accompanied him to the sick man’s house. This gesture was interpreted by the Habsburg successors as the one that helped this dynasty dominate much of Europe for more than three centuries.

3- CHAPEL OF PRAYER

TRANSCRIPTION:

Before beginning the description and history of this interesting chapel, we invite you to stand in front of it in the aisle of the central nave. This chapel is of particular interest because it combines several important elements. First, from the aisle of the central nave and before entering, you can admire one of the most significant reliefs in this parish, dedicated to the Eucharist.

This high relief depicts, in the foreground, a large young angel. He points upward with his arm to Samson, in the background, who is extracting honey from a honeycomb located inside the head of a dead lion. We can read the following quotation: “DE COMENDETI EXIVIT CIBUS ET DE FORTI & JUDIC. 14. V. 14,” that is, “Out of the eater came food, and out of the strong came sweetness.” This phrase alludes to a passage from the life of Samson in which the protagonist obtained honey from the mouth of a lion he had previously killed, causing bees to form a honeycomb inside. Above, in the place corresponding to the bay window, another relief depicting the Ark of the Covenant, the place where the manna was stored, can be seen.

If we consider the ancient dedication of this chapel, we can affirm that this complex is a prefiguration of the Eucharist. On the one hand, Christ achieved the redemption of humanity with his sacrifice on the cross and rose from the dead on the third day. Honey represents the Eucharistic food. The ark where the manna was stored prefigures the new covenant established in Christ’s sacrifice on the cross and permanently signified and renewed by the sacrament of the Eucharist, whose species of bread and wine become new manna.

A second element of particular interest, almost overlooked today, is found to the left of the entrance to this former Communion chapel. It is the base of the pulpit, sculpted for this church. Unfortunately, it was one of the elements destroyed during the Spanish Civil War.

Once inside the chapel, our attention is drawn to its tilework, quite different from the rest of the ceramic plinth surrounding this church. Shades of blue predominate, with beautiful motifs of acanthus leaves, masks, birds, and bouquets of flowers framing the representation of a fish floating or leaping in the sea. In this case, it alludes to faith and the abundance of God’s blessing. This Louis XIV-style tilework predates the rest chronologically and dates from the late 17th century.

Finally, at the top, two paintings capture our attention. These paintings, executed by the Baroque painter Evaristo Muñoz (1684-1737), depict two episodes from the life of Saint John of Nepomuk.

The painting on the left depicts The Banquet of Wenceslas of Luxembourg. In this scene, King Wenceslas of Bavaria invites John of Nepomuk, the confessor of his wife, Queen Joanna. In fact, in the background of the main scene, another parallel and smaller scene is depicted, in which Saint John of Nepomuk appears confessing the queen. Returning to the banquet scene, we see the king entertaining his guest in a richly decorated hall. John is dressed as a deacon and seated at the far left side of the table. With this invitation, the king intends for the confessor to reveal to him the secret of his wife’s confession. When he refuses, John of Nepomuk is condemned to death. Evaristo Muñoz concludes the story in the right-hand canvas, which depicts The martyrdom of Saint John of Nepomuk.

In this second canvas, we see the saint in the center of the composition, surrounded by executioners who intend to tie his hands and feet and then throw him from a bridge into the Vltava River. At the top, an angel presents him with the palm of martyrdom.

In both canvases, a halo of five stars can be seen. This alludes to the stars that miraculously appeared over the river on the night of his murder. These two scenes exemplify John of Nepomuk’s transformation into a martyr to the secrecy of confession and a protector against slander.

Evaristo Muñoz’s work clearly shows his tendency toward theatricality and his desire to surprise and move through lighting effects in moments of greatest tension or interest, following the patterns of Baroque painting.

4- CHAPEL OF THE VIRGIN OF THE BATTLES

TRANSCRIPTION:

We are in the former Chapel of the Immaculate Conception, decorated on this occasion with two anonymous 18th-century paintings: The Burial of Christ, a copy by the Italian painter Titian located on the left side, and the Conversion of Saul, on the right wall.

On this occasion, our attention focuses on the current titular image, the Virgin of the Battles, whose image presides over the current altarpiece and is flanked by the Señera and the flag with the Cross of Saint George. This Virgin pays tribute to the knights of the Centenar de la Ploma and is a copy of the original image, which is currently housed in the new parish of San Andrés, located on Colón Street in Valencia, as previously mentioned.

The knights of the Centenar de la Ploma were part of a local militia. It was a company made up of one hundred crossbowmen charged with escorting and protecting the Señera of the city of Valencia. It was instituted by Peter IV the Ceremonious in 1365 under the name of Centenar del Gloriós Sant Jordi (in Spanish, Centenar of the Glorious Saint George), as it was dedicated to this saint, but it soon became popularly known as Centenar de la Ploma (feather), due to the characteristic feather worn by crossbowmen in their mortarboards, and with this name it has passed into history. It disappeared in 1707 with the Decrees of Nueva Planta.

5- HIGH ALTAR & CHAPEL OF SAINT TERESA OF JESUS

TRANSCRIPTION: HIGH ALTAR

Historical sources referring to the main altar indicate that, in the renovation promoted by the Marquises of Dos Aguas in the 18th century, the construction of a new altarpiece was not contemplated, but rather the existing one, built in the previous century, was used. Historian Elías Tormo describes it in his guide to Levante as an altarpiece with four canvases dedicated to the life of Saint Andrew, attributed to Pedro Orrente (Murcia, 1580 – Valencia, 1645) or to his disciple Esteban March (Valencia, ca. 1610–1668).

However, it was decided to place a supporting canvas by José Vergara (Valencia, 1726–1799), depicting the martyrdom of the titular saint. This canvas was a gift from José Vergara to the parish to which he had close ties, as he was baptized there and was a parishioner from there.

Everything was destroyed during the Civil War. Fortunately, we know the composition conceived by José Vergara thanks to the fact that his preparatory sketch has been preserved in the Economic Society of Friends of the Country in Zaragoza.

Image of the Martyrdom of Saint Andrew (José Vergara)

——————————————————

COAT OF ARMS OF THE ORDER OF DISCALCED CARMELITES

Stand in front of the stairs leading to the high altar. On the floor, a large coat of arms is present: the Carmelite coat of arms.

The Order of Discalced Carmelites of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel was founded in Spain in the 16th century by Saint Teresa of Ávila and Saint John of the Cross. Its coat of arms is full of symbolism:

- Mount Carmel: The mountain in the centre, with a cross, represents the origin of the Order and its path towards Jesus Christ. The lower, brown part, is Mount Carmel.

- Stars: The three stars around the cross can symbolise the prophets Elijah and Elisha, the Virgin Mary (the central white star), or the theological virtues: Faith, Hope, and Charity.

- Crown: The upper crown symbolises the kingship of God and the protection of the Virgin Mary. Sometimes, it is surrounded by 12 stars, representing the 12 privileges granted to the Virgin.

- Arm with sword: Symbolises the fervour of the prophet Elijah for the glory of God and the fight for faith.

- Inscription: The Latin phrase «Zelo zelatus sum pro Domino Deo exercituum» means «I am consumed with zeal for the Lord, the God of hosts,» reflecting the Carmelites’ dedication.

- Colours: The upper white represents purity and righteousness, and the lower brown, the austerity of the Carmelites.

The Carmelite coat of arms is, therefore, a compendium of its identity: history, Marian devotion, and commitment to prayer and service to God.

Asceticism and Mysticism in 16th-century Spanish Literature

In the 16th century, during the reign of Philip II, religious literature flourished in Spain. With Protestantism and a spiritual crisis in Europe, people sought inner perfection and union with God.

- Asceticism: Comes from the Greek «ascesis» (exercise). It is the struggle to eliminate sins and defects to draw closer to God.

- Mysticism: From the Greek «miein» (the mysterious). It is the attempt to achieve an intimate union with God, sometimes with supernatural phenomena such as ecstasy.

To contemplate God, one passes through stages: the purgative way (eliminating what separates us from God), the illuminative way (experiencing God’s gifts), and the unitive way (total union with God). All mystics went through asceticism, but not all achieved union, as it is a gift from God.

TRANSCRIPTION: CHAPEL OF SAINT TERESA OF JESUS

(Her chapel is located fifth from the entrance of the church, on the Gospel side, to the left of the altar.)

She is one of the most important writers of the 16th century. Teresa de Cepeda y Ahumada (1515–1582) was born in Ávila and died in Alba de Tormes (Salamanca). She was a woman of energetic and affectionate character who reformed the Carmelite Order.

She wrote books addressed to her nuns, using a realistic, simple, colloquial, and practical literary style, in which she explains the soul’s process in search of God.

Alongside Saint Teresa, of whom he was a disciple and collaborator, Saint John of the Cross, current patron of this parish, represents the height of 16th-century Spanish mysticism.

Juan de Yepes was born in Fontiveros (Ávila) in 1542 and died in Úbeda (Jaén) in 1591. He joined the Carmelite order and was ordained a priest in 1567. Together with Saint Teresa, he carried out the reform of the Carmelite order. He was imprisoned several times due to conflicts between the Discalced and Calced Carmelites, and during his imprisonment he wrote the most notable parts of his work.

What brought Saint John of the Cross the most fame was his poetry, which he considered a means of union with God. The symbolism in his verse is explained in prose commentaries that he wrote alongside them. These commentaries are, in fact, full theological-mystical treatises.

For example, in the poem “Dark Night of the Soul”, the soul, guided by the dark light of faith, reaches union with the Creator. The commentary on this poem appears in “Ascent of Mount Carmel”, where he relates the summit of this mountain to mystical union with God.

The poems of Saint John of the Cross have harmonious structure and great expressive simplicity. Their rhythm and musicality make his lyricism one of the highest peaks in Spanish poetry. As for the prose commentaries on his poems, since what he seeks to express belongs to the ineffable, he resorts to images, symbols, and allegories, using precise adjectives and speaking with clarity.

6- CHAPEL OF OUR LADY OF TRAPANI

TRANSCRIPTION:

Devotion to Our Lady of Trapani, as the Madonna di Trapani is known in Spain, spread rapidly throughout Europe from the 15th century. This Virgin of Trapani was especially venerated by sailors, a fact that facilitated her worship in port cities like Valencia and explains her presence in the old parish of San Andrés, where the fishermen’s guild had its chapel.

Like the rest of the altarpieces in the old parish, the altarpiece in this chapel was lost during the Spanish Civil War. However, the canvases that decorate the side walls of the chapel are preserved.

In this case, the painter, engraver, and illustrator José Camarón depicts two scenes alluding to the legend of the image of the Virgin of Trapani. José Camarón is an exemplary Rococo painter in Spain. Contrary to the darkness of the Baroque, he opted for bright colors. And although both scenes have religious themes, they almost resemble genre paintings.

In the canvas on the left, a woman elegantly dressed in eighteenth-century fashion strolls through a bucolic and idealized setting. This work is titled Disembarkation of the Image of the Virgin in the Port of Trapani. According to legend, the original image was venerated on Mount Carmel in Palestine and was later moved to a city in Syria. In 1182, Saladin completed the Islamic conquest of this country, so a Christian warrior from Pisa named Guerreggio embarked with it for Italy. A storm forced him to moor his ship in the Sicilian port of Trapani. There he had to wait for months to repair the damage caused by the storm, and it was there that the first miracles occurred. Every time the knight was ready to set sail, bad weather prevented him from doing so. Finally, they decided to leave it with the Pisan consul in that city, to be sent to its destination when possible.

The second part of the legend is depicted in the second canvas, entitled The Miraculous Arrival of the Madonna of Trapani at the Monastery of the Most Holy Annunciation. The statue of the Virgin was to be transported to the port by oxen-drawn cart. However, the animals, guided by a divine power, took the inland route until they reached the church of the Carmelite Monastery of the Most Holy Annunciation, where it remained forever.

7- ARCHAEOLOGICAL WINDOW

TRANSCRIPTION:

General photograph of the church interior with the old altarpiece. Photo by Martín Vidal Corella. F. Cots Archive

We are entering the church from Calle Prócida, the surname of a noble family of Neapolitan origin. Now, move further toward the aisle of the central nave. We notice that the stucco has been lost in the upper part. In fact, this entire section was once occupied by a large organ. If we look at the left margin of the photograph we have shared in this audio guide, we can see part of the structure of the lost organ protruding, which completed the collection of highly ornamental furnishings that, like the altar and pulpit, were destroyed during the Civil War. Subsequent renovation work has revealed part of the classicist structure designed in the 17th century, now functioning as an archaeological window.

Let’s now return to the lower part and pause for a moment to consider the ceramics. The tile collection in the Church of San Juan de la Cruz is one of the most important in Valencian and national heritage. It represents an explosion of shapes and colors, intertwined branches and garlands framing scenes of varied themes, including lush landscapes and remote architecture, waterfalls, and rockeries.

The variation in colors represents a departure from earlier eras. Instead, single colors allow for infinite variations depending on the saturation of the pigment relative to the binder and the color applied over the previous one. Thus, yellow becomes brownish, greenish, orange, bluish, or purple, and copper oxide green becomes yellowish, bluish, or whitish.

Between 2009 and 2010, 4,300 of the 6,000 tiles housed inside the church were restored.

8- CHAPEL OF OUR LADY OF THE FORSAKEN

TRANSCRIPCIÓN:

Devotion to Our Lady of the Forsaken experienced a significant increase in the 18th century. This chapel was built later, but thanks to texts by the Valencian jurist and scholar Marcos Antonio Orellana (Valencia, 1731–1813), we know that the parish already had an altar whose main canvas was painted by Dionís Vidal (Valencia, 1670–Tortosa, 1721).

The chapel’s decoration was completed in the 18th century with a pair of canvases executed by the painter Antonio Villanueva (Lorca, 1714–Valencia, 1785).

On the left, the Miraculous image of Our Lady of the Forsaken is depicted. According to legend, three angels dressed as pilgrims offered to carve the image of Our Lady on the condition that they be given food and lodging. On the third day, the angels had disappeared from the site, leaving the food untouched and the sculpted Virgin finished. Villanueva sets the scene in the 18th century. In the background, a window overlooks the Miguelete. He chose the moment when the angels were still working on the sculpture of the Virgin, in the presence of the host brother, seated in the foreground and dressed in black. The legend is completed with the miracle of the healing of his wife, who was paralyzed and blind.

Opposite is the work entitled The Virgin of the Forsaken Protecting Shipwrecked Sailors. The Virgin of the Forsaken is also the protector of shipwrecked sailors, and, as we mentioned at the beginning of our visit, the fishermen’s guild had its headquarters in this parish.

The Virgin is depicted at the top, accompanied by several angels, while in the center is a galleon adrift in the midst of a great storm. Some of its crew have already fallen into the water and are asking Mary for help.

At the top of this chapel, the vaulted scene depicting the Coronation of the Virgin by the Holy Trinity, by José Vergara, completes the decoration. The pendentives of the dome depict the parents of the Virgin Mary: Saint Joachim and Saint Anne; her cousin Saint Elizabeth; and her husband and son, Saint Joseph with the Child.

9- BENIGNITY BAS-RELIEF

TRANSCRIPTION:

ICONOGRAPHIC INTERPRETATION OF THE RELIEFS

One of the main features of the Church of San Juan de la Cruz is undoubtedly its impressive interior decoration, which is guaranteed to impress. But beyond this surprise, the complex interpretation of the iconographic program stands out, which David Vilaplana, professor in the Department of Art History at the University of Valencia, has studied in depth.

An emblem is an image with a specific symbolic meaning. Collections of printed emblems, each accompanied by a motto, were popular in the 16th and 17th centuries, and artists used them as reference books. The emblems distributed along the central nave, both in the Epistle section (facing the altar, on the right) and in the Gospel section (facing the altar, on the left), refer to the former patron saint of the church, Saint Andrew.

As an example, we highlight the following emblem: “QUI LEGIT INTELIGAT / Math, 24 (15)”: “Let him who reads understand.” In the upper medallion, we see an open book with eighteen St. Andrew’s crosses drawn on its pages. In the words of Professor Vilaplana: “This seems to allude to the mysterious message of the emblems decorating the temple, difficult to read without a notable intellectual effort; however, the key to the program lies in its dedication to the titular saint, whose martyr’s cross appears obsessively reiterated here.”

As a summary of the emblematic program referring to St. Andrew, we find in the vault of the presbytery the main keystone adorned with a rosette and framed by ten seraphim and two small angels. These carry a long phylactery. Currently, only the final part of the text can be read, which alludes to Book I of Kings, chapter 1. 6, which refers to the cherubs that adorned Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem.